#20 Ten takeaways from a master’s program in sustainable fashion in Florence, Italy

Below are ten learnings from my business master’s in sustainable fashion at Polimoda in Florence, Italy:

Materials are everything

Sustainability is all about tradeoffs

Sustainability measurement is an imperfect and contested science

Standards and certifications define best practices but lack harmonization and scale

Supply chain transparency and traceability are the future

Systemic industry change requires policy, and sustainability is increasingly driven by compliance

While consumers report caring about sustainability, other factors ultimately matter more

Circularity has yet to scale and prove environmental superiority

Attention towards nature and biodiversity is growing

Sustainable fashion does not exist; no brand is sustainable; and greenwashing is everywhere

Under each takeaway, I offer a brief description and link relevant resources, including previous articles I’ve written on Medium related to that topic. Read along for more…

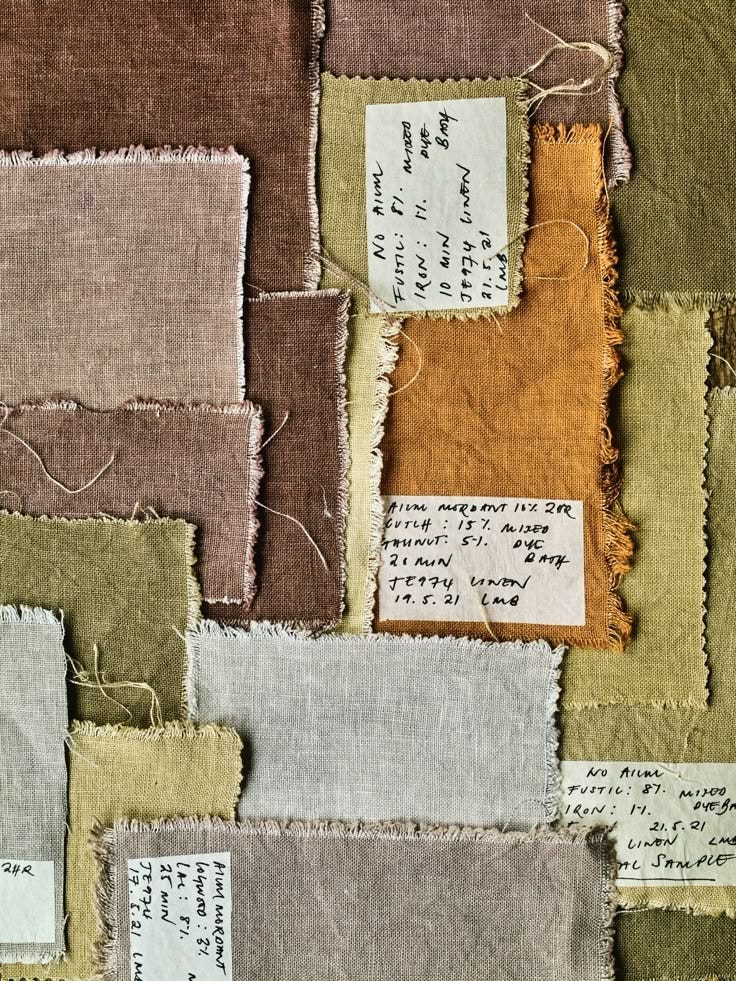

1) Materials are everything

Materials are the essential building blocks of fashion. Originating from natural (plants or animals), synthetic (fossil fuels), or semi-synthetic (manmade cellulosic) sources, they determine all of the factors that ultimately matter most — from cost and supplier choice to performance, aesthetics, and sustainability.

Polyester dominates the global fiber market (~60%), followed by cotton (~20%).

For sustainability professionals, designers, and marketers alike, understanding materials and their distinctions is critical.

→ Related resources: #8 What materials are our clothes made out of?; #5 How is a fashion garment made?; Textile Exchange Materials Market Report 2024

2) Sustainability is all about tradeoffs

Unfortunately there is rarely a perfect sustainability solution—instead, informed decisions need to be made to weigh various (and sometimes competing) environmental and social impacts, at both local and global levels.

Should you prioritize synthetic fiber performance or natural material biodegradability and renewability? What if reducing emissions threatens jobs in low-income regions? How will new regulations affect small producers in developing countries?

Effective eco-design carefully considers tradeoffs to maximize the outcomes that matter most.

→ Related resources: #10 Are natural or synthetic fibers more sustainable?

3) Sustainability measurement is an imperfect and contested science

Tools like the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) are essential — but far from perfect, as they depend on chosen system boundaries, assumptions, and available data.

Leading methodologies such as the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) have sparked debate (see: Make the Label Count) for omitting key factors like microplastics, full lifecycle impacts, renewability and biodegradability, durability, production practices, and social impacts — thereby favoring synthetic fibers.

As the dialogue on sustainability measurement evolves, it will be key to rely on science, ensure all key stakeholders have a voice at the table, and embrace nuanced and critical thinking.

→ Related resources: #9 What is an LCA, and why does it matter (in fashion)?; Europen Platform on LCA; Make the Label Count

4) Standards and certifications define sustainability best practices but lack harmonization and scale

Key sustainability certifications cover the following areas: organic, recycled, circular, and regenerative materials; forest management; material-specific practices (for animals, cotton, leather, flax, etc.); environmental, chemical, and social management. Yet uptake remains slow due to economic pressures and operational challenges — leading to high costs for producers. For example, only ~30% of cotton and ~5% of wool are sustainably certified.

Moreover, the certification system remains vulnerable to fraud and weak auditing, and institutions in the Global North often set these standards, raising questions of fairness and accessibility.

Without harmonization and stronger accountability, certifications risk remaining more symbolic than systemic.

→ Related resources: #11 What are the top sustainability certifications in fashion?; Textile Exchange Materials Market Report 2024

5) Supply chain transparency and traceability are the future

You can’t manage what you can’t measure — and that is especially true in the highly fragmented, multi-tiered, and global fashion supply chains. Transparency is becoming increasingly essential not only to meet sustainability regulations (e.g., ESPR, CSDDD, Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act) and enable progress on Scope 3 decarbonization but also to drive business efficiencies and mitigate supply chain risks (e.g., from trade, policy, climate disruptions).

Emerging startups offer digital (e.g., blockchain-based) and physical (e.g., DNA analysis or additives) tracer technologies to map supply chains and authenticate material origin.

True supply chain progress requires strong supplier engagement and pre-competitive industry collaboration to share costs and data. As the Supima CEO put it: “Without transparency, sustainability cannot be claimed or verified.”

→ Related resources: #13 Is traceability the biggest sustainability challenge in the fashion industry today?; EU Digital Product Passport; Fashion for Good Transparency and Traceability

6) Systemic industry change requires policy, and sustainability is increasingly driven by compliance

As voluntary market-based corporate action has proven its limits, regulatory pressure is on the rise — especially in the areas of product design, supply chain due diligence, reporting, waste, and communications.

Despite setbacks like the recently introduced E.U. Omnibus bill diluting prior legislations, the regulatory wave is here to stay and offers a competitive edge to companies that plan ahead. Leading brands are shifting from passive compliance to active policy advocacy because real progress requires structural change in rules and incentives.

→ Related resources: #3 Why is making fashion more sustainable so hard?; #4 What is the state of sustainable fashion regulation?

7) While consumers report caring about sustainability, other factors ultimately matter more

Price, function, quality, and emotional/social appeal usually outweigh sustainability at the point of purchase. This inconvenient reality has important implications for sustainable fashion product design and marketing: always link sustainability to these greater forms of consumer value (or don’t mention it at all).

At a systemic level, consumers still have a major role to play in driving down over-consumption and -production through behavior change.

→ Related resources: #14 Do consumers actually care about sustainability?; Green Behavior Podcast

8) Circularity has yet to scale and prove environmental superiority

Despite the hype, most circular business models — rental, resale, and repair — remain niche: valued at over $73 billion, they represent just 3.5% of the global fashion market. Moreover, they have yet to demonstrate their environmental benefits due to the high carbon footprint of reverse logistics and an unclear displacement rate (substitution for the purchase of a new item).

Textile-to-textile recycling shows promise (e.g., Circ), but recycling rates are low due to the abundance of cheap virgin synthetics and immature recycling infrastructure. Less than 1% of the global fiber market came from pre- and post-consumer recycled textiles in 2023, with most recycled content derived from PET bottles.

Scaling true circularity will require major recycling tech innovation and a shift in consumer behavior and economics.

→ Related resources: #3 Why is making fashion more sustainable so hard?;

9) Attention towards nature and biodiversity is growing

The industry is starting to move beyond carbon tunnel vision to recognize the broader ecological impacts of fashion. Biodiversity loss, land degradation, and water stress are now on the agenda. Regenerative agriculture is emerging as a promising solution — restoring soil health, supporting ecosystems, and delivering co-benefits for farmers and communities.

Scaling will require clearer definitions, better data and outcomes measurement, long-term investment, and stronger brand–supplier partnerships.

→ Related resources: #12 What is regenerative agriculture, and why does it matter (in fashion)?; Fashion Pact Biodiversity Pillar; Textile Exchange Guidance on Science-Based Targets for Nature

10) Sustainable fashion does not exist; no brand is sustainable; and greenwashing is everywhere

In my first article I laid out the following working definition of sustainable fashion: “an ongoing approach to minimize the negative and maximize the positive impacts of fashion companies on both people and planet across the entire value chain.”

Nineteen articles later, I still mostly stand by this simple definition. However, what has become even more apparent to me is that as long as unfettered economic growth continues to be incentivized, “sustainable fashion” is a misnomer because fully decoupling economic growth from negative environmental impact is virtually impossible (so far). “Sustainable fashion,” therefore, should really be about producing and buying less stuff.

As such, I’d like to end with a slightly revised definition of “sustainable fashion” — segmenting the supply and the demand sides of the market as follows:

Supply (i.e., companies — brands/suppliers): sustainable fashion is the ongoing practice of minimizing overproduction and managing the impacts of production on people and planet

Demand (i.e., consumers): sustainable fashion is buying less, buying better, and using better

Note: Originally published on Medium on November 8, 2025