#22 What is supply chain traceability — and why should you care?

How traceability drives regulatory compliance, verifiable sustainability, and operational efficiency for businesses

Introduction

When I tell people I “work in supply chain traceability,” I’m often faced with a blank stare that reads “what the hell does that mean?”

My simplified answer, “I help companies figure out where their stuff is made,” inevitably leads to the real question: “why does that matter?”

Let’s take an example. Imagine you’re a company waiting on a shipment of critical components. Then one day, a container ship gets wedged in one of the world’s most vital trade chokepoints. Over the next six days, $9.6B worth of goods are held hostage daily. This is exactly what happened in the Suez Canal in 2021. Without traceability, every company whose cargo was on one of the affected ships couldn’t quickly assess the situation, inform customers, and develop an adaptation plan to avoid massive financial losses.

Supply chain resilience is just one driver of the surging attention towards supply chain traceability, which not too long ago was a little known concept. Now it has forged a spot on the executive agenda, given rising sustainability requirements and global macroeconomic supply chain disruptions, which have increased nearly 40% according to Resilinc (especially in life sciences, healthcare, general manufacturing, high tech, and automotive). Similarly, nine in ten respondents in McKinsey’s 2024 Global Supply Chain Leader Survey reported supply chain challenges in 2024.

The point is clear: supply chain traceability matters now more than ever.

In this article, I unpack the core concepts of supply chain traceability, explore the lack of traceability in today’s global supply chains, and dive deeper into how it drives measurable value across three pillars: regulatory compliance, sustainability progress, and operational efficiency.

1–What is supply chain traceability?

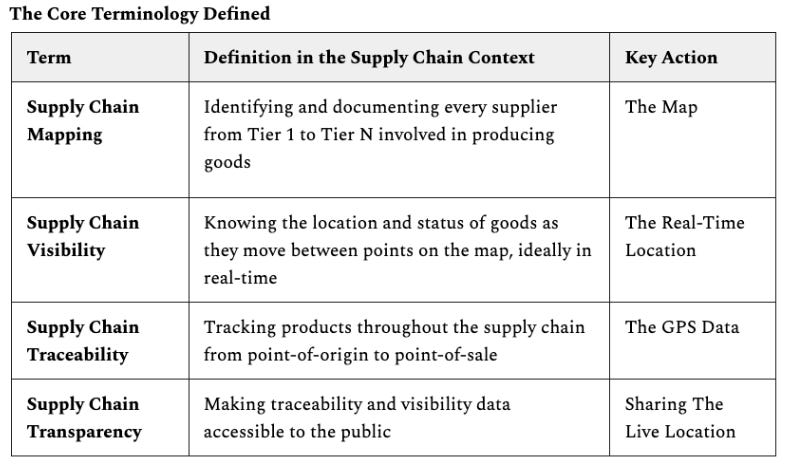

In the supply chain world, the terms visibility, mapping, traceability, and transparency are often used interchangeably, but the distinctions are critical.

Here’s a simple analogy to disentangle the jargon:

Mapping is the roadmap: identifying every potential stop and route

Visibility is the blue dot on the GPS: showing the real-time location of an item

Traceability is the full GPS data log: verifiably recording the history of every specific item (where it came from, when it was handled, and who touched it)

Transparency is the communication of that location data: making the recorded history accessible to the public

All four concepts relate to how goods are produced and distributed and revolve around digitizing supply chains. Executed correctly, mapping is the foundation of traceability, which enables visibility, and results in transparency.

2–How traceable are supply chains today?

The reality is that most organizations today operate with alarming blind spots deep within their supply chains. The most glaring gap is the dramatic drop-off in visibility beyond a company’s Tier 1 (direct) suppliers. Global executive surveys consistently confirm this challenge:

According to McKinsey, 70% of surveyed organizations lack visibility beyond their Tier 1 suppliers, with that number decreasing seven percentage points in the past year

KPMG research confirms this operational blind spot, finding that less than half (43%) of organizations have limited to no visibility of their Tier 1 supplier performance

A core issue is poor digital connectivity. According to EY’s 2024 Supply Chain Survey, 22% of supply chain leaders say their digital connectivity to suppliers is limited to sharing emails and spreadsheets

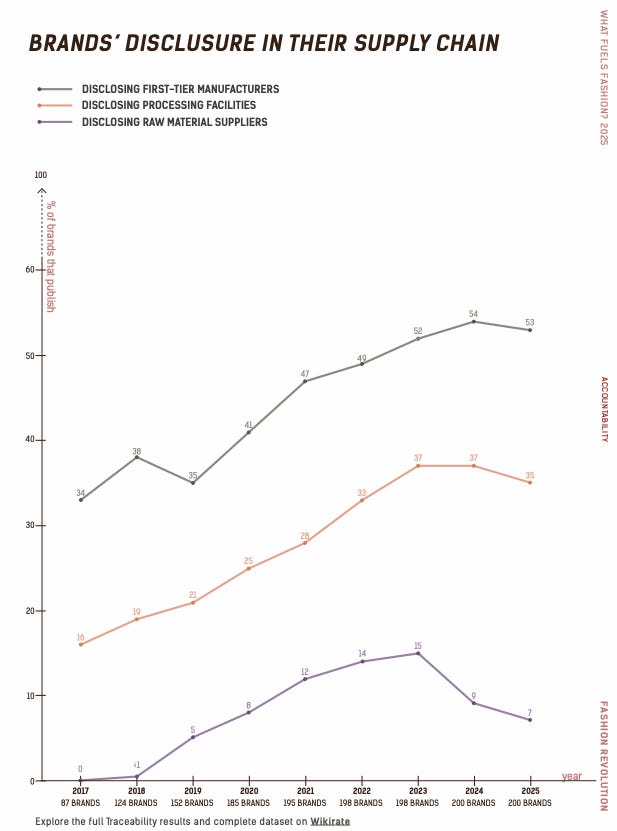

The fashion industry demonstrates this traceability gap in practice. Fashion Revolution’s 2025 What Fuels Fashion? Report found the level of supplier disclosure stalling: 53% of brands disclose their manufacturers, 35% disclose processing facilities, and a mere 7% disclose raw material suppliers (see graph below).

Whether in fashion or beyond, the gap is clear. But what do companies stand to gain by increasing visibility?

3–The business case for traceability

Given the climate of constant disruption and intensifying global regulation, supply chain traceability has become a necessary strategic imperative that drives value across three core pillars: regulatory compliance, sustainability progress, and operational efficiency.

Pillar 1: Regulatory compliance

For decades, the consequences of poor supply chain visibility were limited to reputational damage (think Nike in the 90s). Today, the stakes are financial and legal, driven by strict new legislation that demands verifiable upstream data.

Forced labor

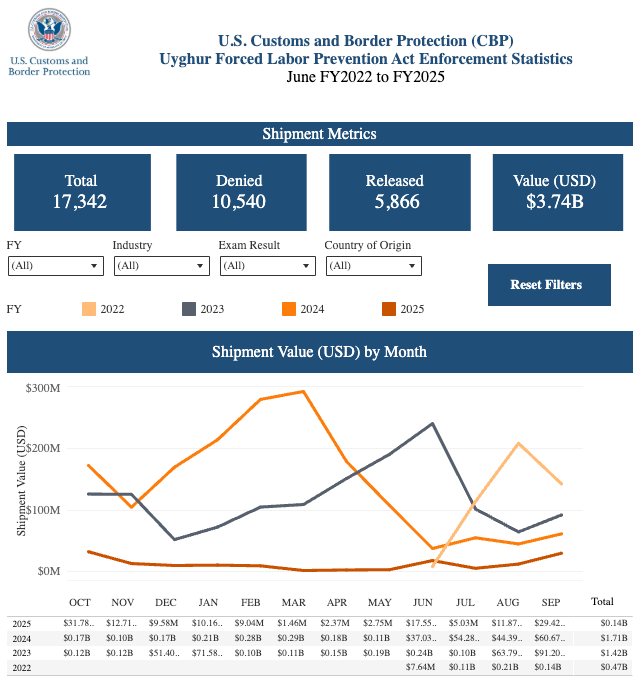

The most immediate and critical risk comes from an intensifying global movement against forced labor. In the U.S., the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) grants U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) the authority to detain and deny entry to goods tied to forced labor. This is not a U.S.-only issue; the movement is global. The European Union is developing its own mandatory forced labor legislation, and nations like Germany, Switzerland, Mexico, and Canada have already introduced or are advancing their own human rights due diligence laws.

The lack of control over deep-tier sourcing is pervasive: for instance, Oritain’s 2023 Cotton Market Insights found that 75% of fashion brands analyzed had at least one garment containing cotton from high-risk regions associated with forced and child labor. Without item-level traceability, compliance is effectively impossible.

The financial consequences for non-compliance are severe. Since 2022, US CBP has detained over 17,000 shipments of goods worth $3.74 billion, with over 60% denied entry into the U.S. and over 55% of all total denials having occurred in FY2025 alone (see graph below). The top three affected industries are automotive/aerospace, electronics, and apparel, footwear, and textiles.

Beyond forced labor, the compliance net is widening to cover broad human rights, environmental impacts, and product integrity across the entire value chain:

Due diligence

In the EU, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) requires large companies to identify and prevent negative human rights and environmental impacts throughout their entire value chains. This is forcing immediate action, yet only 9% of surveyed organizations claim their supply chains are currently compliant with the new rules, with 30% saying they are behind or significantly behind.

Quality control

Traceability is essential for safeguarding consumer health and brand equity by preventing fraud, adulteration, and counterfeiting in sensitive sectors. Major regulations like the U.S. Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) for pharmaceuticals and the incoming FDA Food Traceability Rule mandate package- or lot-level traceability to ensure product integrity and enable rapid recalls.

Deforestation

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) requires companies to prove that seven key commodities (e.g., soy, coffee, cattle) used in their products were not sourced from deforested land. Traceability provides the verifiable geospatial data necessary for proof of origin.

DPPs

Finally, initiatives like the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) are mandating Digital Product Passports, slated to fully go into effect in the next few years. These passports will require comprehensive, verifiable data on a product’s composition, durability, repair information, and material origin—data that can only be generated through robust traceability.

Pillar 2: Sustainability Progress

Whether voluntarily or in response to regulatory pressures, companies will continue to drive towards sustainability goals, which often depend on supply chain visibility. Traceability is the necessary tool for transitioning from making sustainability claims to providing sustainability proof.

Scope 3 emissions

The case for using traceability to drive sustainability progress is strongest in decarbonization. The vast majority of a company’s carbon footprint (on average 90%) resides in its Scope 3 emissions in the supply chain. To accurately mitigate these emissions, companies must have a full map of their supply chain.

Investor and consumer demand

This push for verifiable proof is driven by investors and consumers who increasingly question unsubstantiated claims. According to PwC’s 2023 Global Investor Survey, 94% of investors believe corporate reporting on sustainability performance contains unsupported claims. Traceability provides the verifiable data needed to build trust, especially with investors who use ESG metrics to allocate capital. For consumers, transparency can solidify brand loyalty by providing assurance around product quality and authenticity.

Pillar 3: Operational efficiency

The financial justification for traceability is strongest when it’s recognized as a tool for proactive, data-driven decision-making, not just tracking for the sake of tracking.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the fragility of global supply chains. More recently, conflicts in the Red Sea, port worker strikes, and increasing billion-dollar natural disasters have shown that supply chain disruptions are not the exception but the norm.

Supply chain resilience

Traceability data can allow organizations to identify critical disruptions and vulnerabilities deep in their supply chains. This data can help management to execute quick, surgical action, such as rerouting specific shipments, to mitigate financial losses and ensure business continuity, moving teams from reactivity to proactive risk management.

Strategic planning

Traceability data can enhance inventory management accuracy and refines demand planning and forecasting. Furthermore, this data is a crucial tool for financial and geopolitical risk management: it enables tariff exposure mapping and scenario planning based on verifiable origin data. This tracking is also essential for supply chain security, guaranteeing the authenticity of critical materials like semiconductors or specialized minerals.

Supplier relationships

Finally, the digitization required for traceability creates shared platforms and unified data standards, fostering stronger, more collaborative partnerships across the supply chain, which is essential for managing risk and optimizing global operations.

Conclusion

Traceability is no longer a niche concern for a sustainability officer or a technical project for the logistics team. It is a fundamental strategic imperative.

Ultimately, the investment in traceability is an investment in growth, speaking directly to every leader in the C-suite:

CFO (Chief Financial Officer): Traceability protects the balance sheet by mitigating risk from detained goods and optimizing working capital by preventing millions in inventory holding costs during disruptions

CCO/CLO (Chief Compliance/Legal Officer): Traceability provides the verifiable data needed for mandatory new legislation, from due diligence to forced labor laws, safeguarding the company against fines and legal action

CSO (Chief Sustainability Officer): Traceability is the foundation of responsible sourcing, supply chain decarbonization, and green claims substantiation

CTO (Chief Technology Officer): Traceability can drive the necessary digital transformation of the supply chain, moving beyond manual reporting to implement technologies like Digital Product Passports that will define the future of global trade

CPO (Chief Procurement Officer): Traceability enables stronger, data-driven relationships by providing the visibility beyond Tier 1 necessary to secure critical supplies and build proactive supply chain resilience

The era of operating with blind spots in supply chains is over. The challenge is no longer why supply chain traceability matters, but how quickly companies can achieve it.

Next up: If traceability is critical, why is it still so hard to achieve?

About the Author

I’m Thomas Bernhardt-Lanier, a strategist working to make global supply chains more responsible and resilient. Currently at Sourcemap—a tech startup mapping the world’s supply chains—I write independently about the mechanics and ethics of how things are made and move.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are my own and do not represent those of my employer.